One Art

BY PROF. VAROL AKMAN

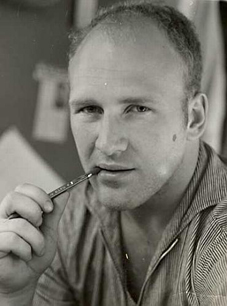

Ken Kesey (1935-2001)

In a kid's story like "Pinocchio" the message is clearly communicated -- if you lie your nose gets bigger. In a novel you have to conceal it, or you're accused of being too obvious.

When Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, the eminent New York Times journalist and critic, wrote the obituary of Ken Kesey, he called him "the Pied Piper of the psychedelic era." It was a fitting depiction of this great novelist, an icon of the countercultural rebellion and the hippie movement of the Sixties.

Kenneth Elton Kesey was born on September 17, 1935, in La Junta, Colorado. During his formative years, he moved with his parents (dairy farmers) and younger brother to Springfield, Oregon. The boys grew up adept at hunting, fishing, swimming and rafting. Kesey attended the University of Oregon in Eugene, where he excelled in wrestling. He graduated in 1957 with a degree in speech and communication. He then went to Stanford University to study creative writing as a student of Wallace Stegner (a.k.a. The Dean of Western Writers):

I took LSD and [Stegner] stayed with Jack Daniel's; the line between us was drawn. That was, as far as he was concerned, the edge of the continent, and he thought you were supposed to stop there. I was younger than he was and I didn't see any reason to stop, so I kept moving forward, as did many of my friends.

While attending Stanford, Kesey volunteered to be a subject of mind-altering drug tests at the Veterans Hospital in Menlo Park, California. The drugs typically gave rise to transitory states resembling those of mental disorder. After the experiments, Kesey took a post as a night helper in the hospital's mental ward.

His close observation of the patients there convinced Kesey that they were being held hostage to a cruel machine that was not even trying to heal them. His firsthand knowledge of the ward became the basis for "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest," the 1962 novel about a maverick who tries to liberate his fellow patients from despotic "control." A landmark saga about the individual versus the system, "Cuckoo's Nest" was admired by critics. It was also adapted into an Academy Award-winning motion picture (with Jack Nicholson playing the lead role) in 1975.

But Kesey was not at all content with the production:

I've never seen it. We were arguing with lawyers and the issue was whether I had been paid adequately. I was fussing with them. They said, Why are you coming on like that, you'll be the first in line to see that movie. I said, I swear to God I'll never see that movie. I did it in front of the lawyers and I'd hate to go to heaven and have these two lawyers calling me on it. I mean, to lie to a lawyer, that's low.

I've never seen it. We were arguing with lawyers and the issue was whether I had been paid adequately. I was fussing with them. They said, Why are you coming on like that, you'll be the first in line to see that movie. I said, I swear to God I'll never see that movie. I did it in front of the lawyers and I'd hate to go to heaven and have these two lawyers calling me on it. I mean, to lie to a lawyer, that's low.

Kesey is the hero of Tom Wolfe's "The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test" (1968). Written in Wolfe's inventive style, the book portrayed Kesey as a holy leader, but one giving out LSD rather than divine counsel to his followers. Focused on a series of missions undertaken by Kesey in the 1960s, it chronicled the transcontinental tour of a group of friends Kesey named the Merry Pranksters, aboard a bus called Further. The expedition took the Pranksters from La Honda, California, to New York City and back. Neal Cassady (the Dean Moriarty of Jack Kerouac's "On the Road") was the bus driver. Back in California, there were the so-called Acid Tests that Kesey gave -- psychedelic parties with The Grateful Dead music and light shows, where the participants were served Kool-Aid laced with LSD.

Kesey wrote quite a few more books during his life. "Sometimes a Great Notion" (1964) is an ambitious novel about an Oregon family. Set in Alaska, "Sailor Song" (1992) focuses on the environment. Co-written with fellow Prankster Ken Babbs, "The Last Go Round" (1994) is about the oldest rodeos in America. Kesey also published nonfiction works: "Kesey's Garage Sale" (1973), "Demon Box" (1986) and "The Further Inquiry" (1990), his own version of the Prankster bus trip. Still, and maybe not surprisingly, "Cuckoo's Nest" remained the zenith of his literary career:

I saw Jerzy Kosinski just before he died -- before he committed suicide -- and talked to him about this. He said in Europe you make one good book, one good movie, and you're set. In America you're expected to best yourself every year and that in itself is crippling.

I don't really know whether Kesey wrote a lot of verse. But the following little poem of his is one of my all-time favorites. The poem is evidently about devotion, regarding which Kesey said in another context (reminiscing about a son who died in a traffic accident in 1984):

He'd been dead about two weeks and I was driving to a wrestling match and I was weeping and talking to him and I said, "Oh Jed, we really loved you" and I thought "That doesn't sound right. Loved." You can't use it in the past tense. We still love him. Death does not stop that love at all.

NOTES

- “Ken Kesey, Author of 'Cuckoo's Nest,' Who Defined the Psychedelic Era, Dies at 66," obituary by C. Lehmann-Haupt, The New York Times, November 11, 2001.

- Many of the quotes are from an interview with Kesey by R. Faggen, appearing in The Paris Review, No. 130, 1994. The Kosinski quote and the final quote are from an online interview with Kesey by M. Rick and M. J. Fenex.

- The poem appears in "The Outlaw Bible of American Poetry," edited by A. Kaufman and S. A. Griffin (Thunder's Mouth Press, 1999).

Geometry

If you draw a line

Precisely safe and parallel to mine,

We can sail together

Clear on past the stars

And never meet.

And since the holes between

These points of distant heat

Are deep and blind,

Sight a course for collision

And hang on tight!

. . . the precision of our loving

Is the lethal kind.