SENA KAYASÜ (ARCH/II)

sena.kayasu@ug.bilkent.edu.tr

Anyone been to the Munch/Warhol exhibit at CerModern?

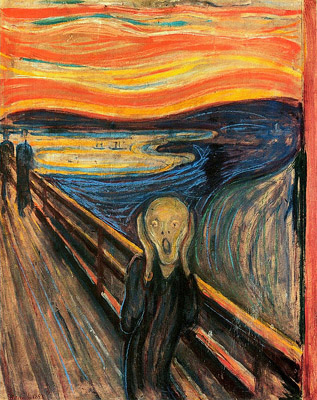

I just managed to go this past weekend. As a student in the Faculty of Fine Arts, I’ve gotten quite familiar with Andy Warhol: a visionary artist who expressed some of the challenges faced by his society, which was soaring in economic well-being and post-war optimism without realizing how everything could come crashing down as soon as the following decade. Personally, I hadn’t heard of Edvard Munch. Only when I went to the exhibition did I realize that he was the creator of “The Scream,” a very famous painting depicting an agonized, distorted figure set against a starkly colored landscape. As it turns out, Munch was an important late 19th-early 20th-century artist who influenced many others, including Warhol.

This show featured the common points between the artists: the Munch prints that inspired Warhol, and Warhol’s expressions or interpretations of them. Both artists worked with prints, so most of the exhibition was in fact composed of variations of the same few pieces. Among Munch’s works were his self-portrait and the “Madonna” series. This section of the gallery was mostly black and white, contrasting with the orange walls and the colorful Warhols that one gets a sneak peek of before actually moving on to that part of the exhibit. Warhol’s works were variations on the Munch prints just mentioned, as well as “The Scream.”

As I later found out, Munch’s life was filled with a tension that he was trying to depict, as seen in his most famous painting. Warhol’s life, on the other hand, was set in a time filled with diversity. What especially fascinated him was the glamour of his society and the consequences of that glamour. He was quoted as saying that life feels like watching television, it is unreal — so it’s understandable that he would question the value of certain things and elevate others, even if doing so was controversial. Maybe precisely because it was controversial. As Edie Sedgewick puts it in “Factory Girl,” “It may just be a painting, but it’s an idea, and the man behind that idea is what’s interesting.”

“Factory Girl” is a thoroughly intriguing movie about Edie Sedgewick, one of Andy Warhol’s superstars. These “superstars” were bohemian, counterculture New York City eccentrics. They were promoted by Warhol, who generated publicity for his work in this way. They also proved his idea of “15 minutes of fame”: that everyone will be famous, even if just for a glorious moment.

This movie really got to me on several levels. The first is that I cannot see or hear anything about Warhol without immediately being reminded of the way he was portrayed by Guy Pearce. This was controversial and received mixed reviews, some of which criticized the way Warhol was depicted as being the one who ruined Sedgewick, who entered a downward spiral after she met him until her death at the age of 28. The film is more about Sedgewick and her experience of the Factory (Warhol’s studio in New York) than about the artist himself, but he is presented as an integral part of her life. Furthermore, he is shown as a greedy and selfish man who uses her life energy and her family’s money for his own purposes, mainly to create his “art.” Because of this, and his rejection of her when, straying ever so slightly from his circle, she befriends Bob Dylan, he and the environment he creates are implied to be the causes of her downfall.

Now, I haven’t done extensive research on Warhol and the pop art period; I don’t know to what extent these depictions are true. Actually, they seem like exaggerations aimed at portraying Sedgewick as a victim, even if it means villifying other characters, above all, Andy Warhol. Still, Sienna Miller’s portrayal of Sedgewick as a tormented young woman was so powerful and, from what I’ve found out since, so accurate, that I can’t help but be drawn in by this account. Possibly because they were so marginal, people don’t seem to hesitate before judging and blaming “members” of the Factory. Ironically, that was Warhol’s point: we will all be famous, but for what, and at what price? His paintings are not just repetitions in different colors. They show the different lenses through which we see celebrities or the realities of everyday life. To go back to Warhol’s idea, life is so unreal, so like watching something remotely rather than actually living it, that we can see it in fuscia or bright green or yellow, and it won’t be any less ridiculous or any less transient.

Now, I haven’t done extensive research on Warhol and the pop art period; I don’t know to what extent these depictions are true. Actually, they seem like exaggerations aimed at portraying Sedgewick as a victim, even if it means villifying other characters, above all, Andy Warhol. Still, Sienna Miller’s portrayal of Sedgewick as a tormented young woman was so powerful and, from what I’ve found out since, so accurate, that I can’t help but be drawn in by this account. Possibly because they were so marginal, people don’t seem to hesitate before judging and blaming “members” of the Factory. Ironically, that was Warhol’s point: we will all be famous, but for what, and at what price? His paintings are not just repetitions in different colors. They show the different lenses through which we see celebrities or the realities of everyday life. To go back to Warhol’s idea, life is so unreal, so like watching something remotely rather than actually living it, that we can see it in fuscia or bright green or yellow, and it won’t be any less ridiculous or any less transient.

The exhibition showed his work from a time later than that of his most famous pieces. However, these later works feature the same variety and courage in colors and tone, while maybe being more grounded in theory. Since most of the Munch pieces displayed at CerModern were black and white, it made a great difference to see them in outrageous colors. These tones can instantly translocate the images from the grave-looking 19th-century editions to the psychedelic pop art period. Well, the ones other than “The Scream,” anyway.