Thomas Zimmermann, Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology

BY MELİS ERDEM (ARCH/II)

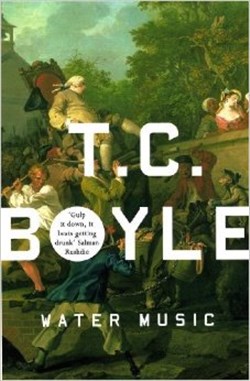

I believe one of the most influential books I read when I was quite young, about 16 or 17 years old, was “Water Music,” by the American novelist T. C. Boyle. In the book, there are two separate stories, which intertwine at the very end. One is about the Scottish explorer in Africa, Mungo Park, a historical figure. He was real; the story is (partly) fiction. It’s about the totally chaotic, painful exploration of Africa in the 18th century. The other part of the story, set in London, is about a complete loser who fell through all the nets that could just about guarantee you a more or less acceptable social life. He is at rock bottom, just trying to survive, although he’s not very successful even in that. He’s an alcohol addict. Well, the story is as disastrous as Mungo Park’s expedition in Africa. And the two stories intertwine in a very fascinating way. The characters in this book are extremely colorful and controversial, and the story is funny, exciting and also shocking. It’s very graphic to some extent, especially when some indigenous tribes in Africa experiment with white expedition members.

I believe one of the most influential books I read when I was quite young, about 16 or 17 years old, was “Water Music,” by the American novelist T. C. Boyle. In the book, there are two separate stories, which intertwine at the very end. One is about the Scottish explorer in Africa, Mungo Park, a historical figure. He was real; the story is (partly) fiction. It’s about the totally chaotic, painful exploration of Africa in the 18th century. The other part of the story, set in London, is about a complete loser who fell through all the nets that could just about guarantee you a more or less acceptable social life. He is at rock bottom, just trying to survive, although he’s not very successful even in that. He’s an alcohol addict. Well, the story is as disastrous as Mungo Park’s expedition in Africa. And the two stories intertwine in a very fascinating way. The characters in this book are extremely colorful and controversial, and the story is funny, exciting and also shocking. It’s very graphic to some extent, especially when some indigenous tribes in Africa experiment with white expedition members.

I was born in a small town in the province of Bavaria in southern Germany. Life there was pretty predictable. People I went to school with showed hardly any motivation to find jobs anywhere other than my hometown. So their lives and careers were pretty predictable. I knew that I had to break out of those bounds, that I was not destined to find a job in the local bank or become a schoolteacher there. I had to travel. And this book really triggered my fascination for many things: traveling and experiencing non-European cultures, early modern European history—and also Baroque music.

At one point in the book, the British king—I think it was George III—appears. He suffered from a mental illness in his later life; he was known as the “mad king.” So when he hears an orchestra playing, he just stumbles in, and demands Handel’s famous “Water Music” suite, yelling “Water music, water music”— hence the title of the book. This is described in a beautiful manner—the king is totally deranged, and the entourage is trying to keep him calm. But he has these strange outbursts.

I’m very much into Scottish culture, not least because of this book. My, let’s say, first scientific thesis had to do with Scotland. In Germany, at the very end of high school, students have to write a  study paper of about 30 pages in the major subject they chose. I took English as a major subject in high school, along with history and German literature. I decided to write on the history of Scottish single malt whisky. And in a way, this was triggered by the character I mentioned earlier, Mungo Park. He’s an adventurer, but he’s naïve to a certain extent—he’s totally unprepared for his expedition to Africa. The expedition members have no idea what difficulties, what illnesses, what hardships are waiting for them. Park’s calm and totally detached behavior, his detachment from the situation, actually saves his life.

study paper of about 30 pages in the major subject they chose. I took English as a major subject in high school, along with history and German literature. I decided to write on the history of Scottish single malt whisky. And in a way, this was triggered by the character I mentioned earlier, Mungo Park. He’s an adventurer, but he’s naïve to a certain extent—he’s totally unprepared for his expedition to Africa. The expedition members have no idea what difficulties, what illnesses, what hardships are waiting for them. Park’s calm and totally detached behavior, his detachment from the situation, actually saves his life.

I would say that if I hadn’t read “Water Music,” life would have led me in a different direction. Eventually, I would have ended up somewhere in Bavaria. Probably I would still have studied archaeology, but I would have ended up in a Bavarian museum or archaeological mission. This book was an opening for me to look over the rim and experience a growing fascination with different continents, different cultures, different countries and different histories. It was a real keystone, in a way, in the process of embarking on the scientific career that finally brought me to Turkey.