One Art

BY PROF. VAROL AKMAN

“OTHER LOST SOULS LIKE OURSELVES”

AN INTERVIEW WITH DANA GIOIA

Dana Gioia is an internationally acclaimed and award-winning poet. He has recently been appointed the Judge Widney Professor of Poetry and Public Culture at the University of Southern California. This week I'm just presenting my email interview with him. After the winter recess, I'll devote my first column again to Gioia (pronounced JOY-uh).

Dana Gioia is an internationally acclaimed and award-winning poet. He has recently been appointed the Judge Widney Professor of Poetry and Public Culture at the University of Southern California. This week I'm just presenting my email interview with him. After the winter recess, I'll devote my first column again to Gioia (pronounced JOY-uh).

1. You were a student of Elizabeth Bishop. Could you please tell us what it was like to be in the presence of this great poet? What was the most important thing about poetry that you've learned from her?

When I knew Elizabeth Bishop at Harvard, she was not yet recognized as a "great poet." Robert Lowell was the undisputed "great" poet on the faculty, and Bishop was an estimable "minor" poet in the eyes of the faculty. My graduate adviser told me quite strongly not to study with her. She was not considered "serious." I had loved her poetry since high school. She was -- oddly back then -- one of the first contemporary poets I read not because I had found her in anthologies or read about her in criticism but because a composer I greatly admired, Ned Rorem, had set her work to music. I had fallen in love with certain poems, such as "Questions of Travel" and "Visits to St. Elizabeths," and I wanted to meet her. There were only five other students in the class, which shows you how little she was regarded in status-obsessed Harvard. I liked her immediately, and we gradually became friends, often going out for tea after class. She was a polite, slightly old-fashioned woman. She disliked talking about poetry outside the classroom, but we never lacked for topics of conversation. I never felt that I was in the presence of a "great" writer. That stance would have been too pretentious for Elizabeth. She was simply herself. She never said anything to make an effect. It was from her that I first understood that authenticity was at the heart of the best writing. Meaningful poetic originality and personality grows out of a writer's character.

I also learned from Elizabeth that a true poet is unconcerned with literary and critical fashion. A real writer has an independent way of looking at the world that need not be reconciled with what James Fenton has so memorably called "ghastly good taste." Actually, that's what I learned from her at the time. But gradually I came to realize that she was doing something far more obvious and far more profound that I was unable to see in my hyper-intellectual graduate school days. Back then I could see her behavior only in relation to the intellectual world of Harvard. I now know that what she really taught me was that a poet isn't essentially an intellectual who sees the world in terms of categories and ideas. A poet understands and articulates the world as a whole -- not dividing ideas from emotions, perceptions from the senses, the intellect from intuition or imagination. I wasn't ready to grasp that notion in my early twenties, but over the years, as I struggled to recognize that in my own journey as an artist, I saw that Elizabeth had been there all the time. Good teachers are like that. We don't get all of what they teach us in the classroom. Their lessons hide in the corners of our lives until by luck or sheer effort, we find them, one by one.

2. You worked with the composer Alva Henderson on the opera Nosferatu. We also know that composers have set your poems to music. I have a hypothetical question, based on your love for and involvement with jazz. If Amy Winehouse were alive today what poem of yours do you think she could have used as lyrics?

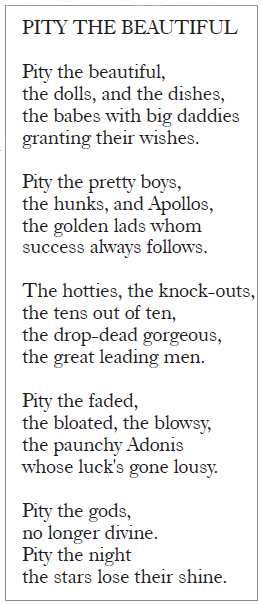

It is odd that you would ask me this question. Right after Amy Winehouse's death, The New York Times ran a blog about her that reprinted a poem of mine called "Pity the Beautiful." Most readers thought it had been written about her (which it hadn't), and there was much discussion about her and the poem. The whole thing took me by surprise. I admired her singing immensely -- so raw, so passionate, so painfully true. It was clear from the start that she was doomed. Her death wasn't an accident. It was the only possible end to her plunge into the dark side. I have always been drawn to the poets maudits

-- Poe, Baudelaire, Trakl, Crane, Kees. They see things that the daylight world denies. Winehouse was a member of that "visionary company."

I'm not sure what she might have done with one of my poems. She made her material her own. If I have learned anything from the musicians and composers I have worked with, it is that I can never predict what texts will interest them. I'll offer a love poem, and the musician will choose one about the apocalypse. Offer a spiritual poem, and the composer wants the one about sex. And now what words can I offer to the dead? Perhaps I should offer her the same words that a stranger chose from my work to accompany his eulogy? Here is "Pity the Beautiful," a poem written in memory of another doomed woman I knew nearly forty years ago. I wrote it to be as lyrical and transparent as a song -- qualities that were once important to poetry but now not merely absent but critically despised.

But why worry about the critics? We write for other lost souls like ourselves.

3. The management guru Henry Mintzberg says (The Huffington Post, July 7, 2010): "A leader is not the hero who rides in on the great white horse to save the day. He or she is a person who gets personally and deeply engaged, so as to engage others, in order to bring out the best in them." Having served as a leader both in industry (marketing executive and eventually vice-president at General Foods from 1977-1992) and government (chair of the National Endowment for the Arts from 2003-2009), would you agree with this counsel?

There are many aspects to leadership, and there is no single successful style. A leader needs to lead, of course, to set the direction and the vision of the organization. That is crucial, and any leader who expects that vision to emerge mysteriously from the ranks of an organization is probably deluded. But a leader also needs to enlist the organization in the vision. He or she must articulate the vision and goals and then make the people who work there share those objectives. Persuading them is an essential part of a leader's job. Only when most of the people in an organization share common goals is a leader able to accomplish anything. So much of what a leader does is to master language -- first to shape the mission, then to explain it to everyone involved, and then repeatedly to re-engage their minds and imaginations at each stage of the journey. I guess in this sense a leader is a sort of a poet, one who calls something new into existence through the truth and magic of words.