Me, Elif Batuman and King Kong

BY CÜNEYT YILMAZ (ECON/IV)

cuneyt_y@ug.bilkent.edu.tr

My life doesn't resemble that of Raskolnikov or Jean Valjean at all - and hopefully won't ever. But sometimes it feels surprisingly novel-like, if you know what I mean.

On the third day of the bayram holiday, I woke up at the same time as a Chinese worker would to produce more iPads. I was planning to catch a train from İzmir to Ödemiş, a district that claims to be a part of İzmir with no actual relevance whatsoever. Being the universally acknowledged procrastinator that I am, however, I once again managed to miss a means of transportation, this time by a difference of twenty minutes. So Heraclitus was wrong (ditto my ex-girlfriend): some things will never change. Instead, I had to buy a ticket for a later train.

The train leaves from a terminal in Basmane, a district located in the heart of the city, if not in those of its citizens. It's a neighborhood where you shouldn't go out on the street alone, just to make sure you're accompanied by someone you know rather than some random stalker who will later on follow you anyway. Despite knowing this and that I am a walking magnet in the shape of a human being that attracts nothing but trouble, I still couldn't resist the hunger inside my belly. Therefore I took myself out of the terminal, to the chaos of three-star hotels and unpromising kebab restaurants. Amid the hubbub of the daytime Basmane crowds, I found a small place where I could eat my brunch and read the book I've been possessed by lately: Elif Batuman's "The Possessed."

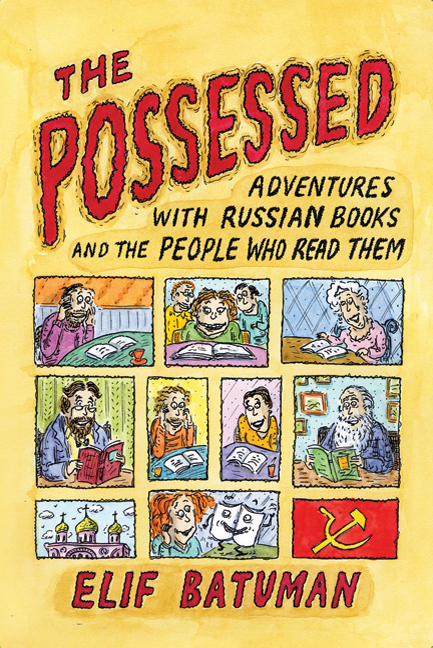

Elif Batuman is, quoting her verbatim, "a six-foot-tall first-generation Turkish woman" who grew up in New Jersey. She graduated from Harvard and got her PhD from Stanford. At the moment, she's a writer-in-residence at Koç University. She published her first book, "The Possessed: Adventures with Russian Books and the People Who Read Them," in February 2010, at the age of 33 (so I still have 11 years to come up with a book of the same caliber and a title of similar wittiness). It's a memoir of her literary encounters as a graduate student, a bizarre yet funny selection of topics including Isaac Babel, Leo Tolstoy and King Kong.

I picked the furthest possible table from the door and ordered menemen, a mixture of tomatoes and eggs cooked in a metal pan. (My version of this dish brought me the Nobel Peace Prize for its role in bringing together exchange students of varied nationalities during my stay in Portugal.) A Turkish radio station was playing in the background while I was trying to concentrate on the book and the menemen simultaneously.

I was reading the part about Batuman's summer spent in Samarkand learning the Uzbek language. While Batuman was speaking of her trip to Samarkand, the pop singer on the radio, Hande Yener, was saying that the only place she'd go was an airport and that she needed a new place to live. Did she have an Uzbek counterpart? Or, in other words, was it possible to translate Hande Yener herself into Uzbek, not just her songs?

The next song was by Deniz Seki, who has recently gotten out of jail and is therefore busy with self-development. She sang, as if to give the listener an encouraging touch on the shoulder, "there isn't any road on earth that you can't overcome," unwittingly referring to Muzaffar, the philosophy graduate with whom Batuman studied Uzbek and who was constantly complaining about his problems.

Struck by these coincidences and also by the way the waiter was staring at me because of my overstay, I left the restaurant. The language I heard outside, a combination of slang with corresponding gestures and mimicry, made me feel like Elif Batuman in Uzbekistan. Was that feeling the reason why someone would travel? Our motivations were different, obviously -- or were they? She went to Uzbekistan because she was studying Russian literature. Me? I was taking the train because I wanted to see some friends. Obviously, there was quite a contrast between her journey and mine, but when you come to think of it, you realize that the same feeling of being a stranger may come over you anywhere -- be it Samarkand or Basmane.

This reminded me of the part in the book where the author mentions her comparison of "Anna Karenina" to "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland" at an international Tolstoy conference and relates how this caused unease among the participants. Some of the latter had gone mad, although she "wasn't suggesting a one-to-one correspondence between every character." And I realized that the same was also true for me. You'd want your life to resemble your favorite books, as Batuman suggests, but it's never possible to live exactly the same life as your favorite character in a book, is it? If I ever acted like Holden Caulfield, for example, the outcome would probably be a punch in my face, if not a kick in some sensitive part of my body.

The back streets of Basmane were brimming with spices sold on counters, with fresh juices offered at the price of a lira. But the buildings were old and, believe me when I say this, grumpy. The atmosphere gave me an uneasiness nothing else but swimming does. I figured that if the regime in Turkey were ever to change to communism, Basmane would be the first place to adapt to it. If only I had a camera with me, I lamented inwardly, envying Japanese tourists for the first and probably the last time in my life, because they take pictures of anything. To my dismay, when I got back to the terminal I saw some tourists, of whom a large portion were Japanese, taking pictures as they always do, fascinated by what they were seeing: Basmane, that is.

I put on my earphones and started shuffling through my iPod's library as the train began moving. After a few tedious tracks, "Swans," my favorite Camera Obscura song, began playing. "Oh, you want to be a writer. Fantastic idea!" Tracyanne Campbell sang, while I -- with a smirk on my face -- nodded my head in agreement, imagining Elif Batuman telling me the same thing. "Maybe you should travel with me," the song continued, and like Holden Caulfield wanting to befriend a writer he likes, I imagined traveling with Elif.

At the time, I wasn't planning on writing about all this. That is, however, until last week, when I was surprised by what Marmara Restaurant had as a dinner selection: Uzbek Kebab. If that's not a sign for me to follow in Batuman's footsteps, I ask you, what is?

If you haven't been possessed by a book lately, go straight to the library and borrow Elif Batuman's "The Possessed: Adventures with Russian Books and the People Who Read Them." That's the kind of prose that I want to come up with if I can ever get myself to graduate school and manage to write a book about it. Now, how do we apply for a PhD in literature?