One Art

BY PROF. VAROL AKMAN

Linda Gregerson (b. 1950)

Poetry has always known that the subject is a made thing: made by longing for another, made by sorrow and the friction of daily getting-on-with-it, made above all by speech.

In his 2011 book "Justice for Hedgehogs," the philosopher Ronald Dworkin uses this wonderful line: "The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing." If poetry is one big thing, then Linda Gregerson definitely knows that. (Mark Strand remarked that her poetry is among the very best being written.) But she also knows many other things. She is an expert on lyric poetry and Renaissance literature. She studied music history and theory. Between 1972 and 1975, she was a member of a theater company, with performances in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia and other cities. ("The theater was the first place I learned how to think.") For six years (1982-1987), she was a staff editor (poetry) for The Atlantic Monthly.

Linda Gregerson was born on August 5, 1950, in Illinois. She received a BA from Oberlin College, an MA from Northwestern University and an MFA from the University of Iowa Writers Workshop. Her 1987 doctoral degree was from the Department of English at Stanford University. Since then she has been at the University of Michigan, where she is the Caroline Walker Bynum Distinguished University Professor of English Language and Literature.

Gregerson is the author of several poetry collections: "The Selvage" (forthcoming 2012), "Magnetic North" (2007), "Waterborne" (2002), "The Woman Who Died in Her Sleep" (1996) and "Fire in the Conservatory" (1982). She has also written two volumes of literary criticism.

Her numerous awards include those from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Poetry Society of America and the Modern Poetry Association. She is the recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim, Rockefeller and Mellon Foundations, the Institute for Advanced Study, the National Humanities Center and the National Endowment for the Arts. For "Waterborne," she won the $100,000 Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award. Her poems have appeared in such leading journals as The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, Poetry, Granta, The Paris Review, The Yale Review and The Kenyon Review. Gregerson characterizes her poetry as blending "maximum consequence with minimal gesture."

Society of America and the Modern Poetry Association. She is the recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim, Rockefeller and Mellon Foundations, the Institute for Advanced Study, the National Humanities Center and the National Endowment for the Arts. For "Waterborne," she won the $100,000 Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award. Her poems have appeared in such leading journals as The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, Poetry, Granta, The Paris Review, The Yale Review and The Kenyon Review. Gregerson characterizes her poetry as blending "maximum consequence with minimal gesture."

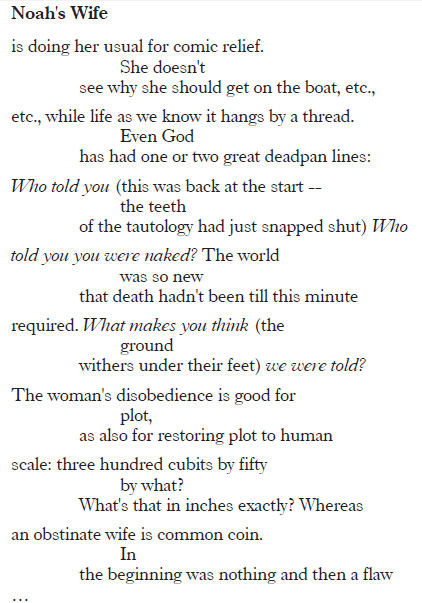

I have selected this week's poem for the obvious connotations it offers for us. Since early childhood, we've heard so much about Mount Ararat, traditionally known as the landing place for Noah's Ark at the end of the flood. But what about Noah's wife? In the Genesis story, she is scarcely mentioned and never named. Well, read the poem and let (paraphrasing what Jorie Graham said of "Waterborne") Gregerson's brilliantly paced vision execute its balletic moves of mind.

The following exchange with Professor Gregerson was via email.

1. If you were to write a poem about the infamous serpent, what sort of overall treatment would it receive from you, sympathetic or disapproving? Why?

I think I would begin the way I did with "Noah's Wife" and try to find some clue in the folk traditions. The comedy attached to Noah's wife comes straight out of the medieval mystery plays of England. Twice-told tales are often remarkably witty and subversive in their folk incarnations. Essentially, I'd try to think across the grain, looking for some element of plausibility in the serpent's logic.

2. Are you able to recite (some of your poems) by heart? Could you please name a favorite poem by a great dead American poet? What essential quality makes it precious to you?

Certainly. Poetry inscribes itself in memory if it's worth its salt.

A favorite poem by a great dead American poet: "One Art" by Elizabeth Bishop, one of the greatest villanelles ever written. It's heartrending because it is both disciplined by form and anguished beyond all possible formal control. But perhaps your column is already named for this poem? [Yes, indeed! -VA]

3. When and how do you settle on the idea that a collection of poems written over a period is now ready to appear as a book? And selecting the book title: how exasperating a process is it for you?

When a collection is perhaps 2/3 or 3/4 of the scale and density it ought to be, I begin to experiment with sequencing, which tells me in turn what kinds of poems are still missing, what the manuscript needs to move further toward completion. Choosing the title is part of that process; ideally it identifies a trajectory in which the poems already wish to move. But it also identifies the distance the manuscript has yet to go. And, yes, it is often maddening! I've changed the title of my forthcoming book several times.

NOTES

- The opening quote is from an interview with Gregerson by David Baker, appearing in The Kenyon Review, March 2007.

- "Noah's Wife" is from "Waterborne." It originally appeared in the December 1998 issue of Poetry magazine.

- At least one rabbi thought that based on Genesis 4:22, Noah's wife was Naamah (literally meaning "pleasant"), so called because her demeanor was pleasing to God. Other authorities reject this view, cf. http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com.