Ancient Umwelt

Culture shock can be a harsh mistress: though globalization has enabled an extensive exchange of information between world cultures, some local customs still remain incomprehensibly alien to any foreigner despite being nothing out of the ordinary in their native territory. Even outsiders persistent enough to breach the language barrier meet a second line of defense in the form of various similes, expressions and sayings unique to every city, town or village, apparently coined on a whim and used without reason or rhyme -- Turkish, for example, has a curious obsession with drakes (male ducks, that is), and the object of one's affection is often likened to these waterfowl due to their supposed beauty and elegance. This problem is only exacerbated further when one considers the customs and language of a culture distant not only in space, but also in time: historical texts and especially mythological accounts are testament to just how much culture, language and common knowledge have changed between then and now. This week's column, therefore, will be devoted to unusual views of our ancestors, offering a brief look at how they saw the world around them and what they thought of it -- particularly with regard to various beasts that shared the earth with them.

Such information was compiled in illustrated books called bestiaries, similar in content and structure to modern animal encyclopedias, though with substantial discrepancies stemming from the lack of accurate information in such times: medieval bestiaries, after all, do have a penchant for starting off with a startlingly keen insight about the nature of an animal, and then getting everything else about it wrong. It was well known, for example, that honeybees could only sting once and perished soon after, though the purported reason was that the workers, sensing that they had failed the hive in one way or another, willingly sought to commit suicide and so absolve themselves of their guilt. It only got worse from there: Bees were also the smallest of birds, and were formed from ox carcasses left to decay -- a myth perpetuated by the existence of several types of bee-mimicking flies that indeed emerged from decaying carcasses. Likewise, the symbiosis between certain birds and crocodiles was noted over two millennia ago, though since the description of the crocodile essentially boiled down to "big, dangerous creature with four legs," and the illustrators had to work with the descriptive text alone, their depictions of the animal usually ended up being a dragon and even featured wings at times.

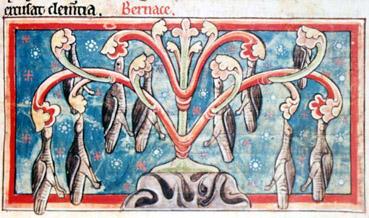

Dolphins were one of the biggest enemies of crocodiles and bore razor-sharp fins on their backs, which they used to slash through the poor dragon-reptiles. They could also soar over ships to attack men, which is really closer to the truth than the modern perception of dolphins. (Despite their cute looks, dolphins engage in such lovely behaviors as "calf tossing," initially believed to be a game where an adult dolphin plays with its offspring by tossing it into the air, much as a human parent may do. It later turned out that the "game" was played mainly by male dolphins, who removed competition by smacking the offspring in question out of water until it perished.) Yet another bizarre creature, this time a victim of wild speculation, was the barnacle goose: as stalked barnacles rather resemble small geese, and the bird was virtually absent in Ireland during summer months (they're migratory, if you're curious), a myth involving geese growing on trees as shellfish and dropping off in winter to take wing soon developed. This incidentally made the geese acceptable to eat on certain fast days, under the excuse that it was not truly a bird (a similar excuse is also used for the capybara, which to devout South American Christians is a giant, four-legged, rat-like fish frequently consumed when red meat is otherwise forbidden). Speaking of Christianity, it is also notable that animals were frequently made into religious allegories, usually either of Christ or the Devil. Pelicans, for example, are representative of Christ, while onagers are satanic.

In any case, those curious about ancient accounts of various animals, plants and minerals may simply type "medieval bestiary" into a search engine of choice, the first result usually being an excellent website that offers not only descriptions, but also several galleries of illustrations featuring the relevant beasts. Have a nice week!