One Art

BY PROF. VAROL AKMAN

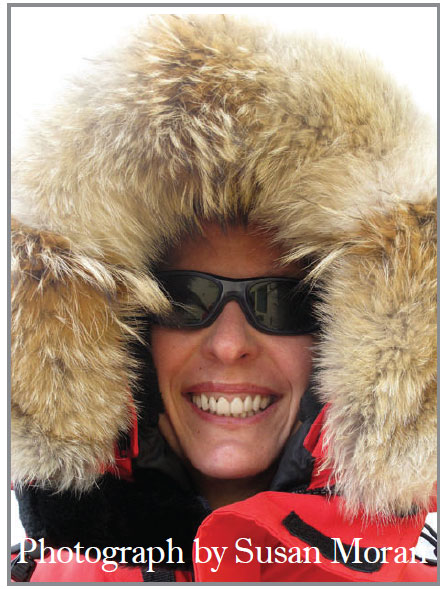

Katharine Coles

So, what am I after? Truth, of course. Cheek-to-cheek contact with the sublime. Insight into the nature of reality. The most precise language possible to depict that reality…

It is definitely getting cold around here, and what Katharine Coles is wearing in this photo will soon make a lot of sense in Ankara. But you see, she was wearing that last winter (November-December 2010) when she traveled to Antarctica as part of the National Science Foundation's Antarctic Artists and Writers Program. The trip was nearly supernatural ("Mostly, I've just been saying 'WOW!'"). She even had two penguins hop into her Zodiac boat for a ride across the Antarctic Sea, an exceedingly singular event if you are looking for one.

Selected in 2006 as Poet Laureate of Utah, Coles is professor of English at the University of Utah. During 2009 and 2010, she also served as the inaugural director of the Harriet Monroe Poetry Institute at the Poetry Foundation in Chicago. Coles received her BA (1981, English) from the University of Washington, her MA (1983, Literature) from the University of Houston and her PhD (1990, English Literature and Creative Writing) from the University of Utah.

Coles's books of poetry include "Flight" (forthcoming, 2013), "Fault" (2008), "The Golden Years of the Fourth Dimension" (2001), "A History of the Garden" (1997) and "The One Right Touch" (1992). Linda Gregerson said of "Fault":

Whether she's contemplating the history of cosmology or the stern topography of western canyons, the "touched wires" that detonate the bomb that destroys a city square or the touched chords of married love, Katharine Coles writes with stirring passion and impeccable clarity.

The following interview was carried out via e-mail.

1. You have written some beautiful animal poems. (My personal favorite is "Elegy for a Dog Larger Than Life.") What is your favorite animal poem, written by a great dead poet? Why?

There are many animal poems I love -- Marianne Moore, for example, is so precise in her observations of animals, almost scientific; and Dickinson and Bishop are also both terrific with animals -- but I would have to choose as my favorite Yeats' "The Wild Swans at Coole." In high school, I committed it to memory, so I have a nostalgic connection with it, and I am always delighted when it comes back into my mind inone situation or another. I love the way Yeats uses his close observation of the swans ("the bell-beat of their wings above my head") to say something about the nature of love and disappointment, and most especially to acknowledge that beauty exists in the world in spite of, and maybe even because of, personal disappointment.

swans ("the bell-beat of their wings above my head") to say something about the nature of love and disappointment, and most especially to acknowledge that beauty exists in the world in spite of, and maybe even because of, personal disappointment.

2. In a (hopefully impossible) world where poetry in all its forms is forbidden, what would you choose as a profession? Why?

There were several professions I considered seriously then rejected to pursue poetry in a concentrated way. The first was Marine Biology -- again, this has to do with my fascination with animals and especially the mysterious creatures of the sea, who are so alien to us because they are usually hidden under the water's surface. Second was acting -- I did train as an actress in college and do some performing, but I was already writing poetry very seriously then, and I eventually decided that acting was too intimate and revealing to be a comfortable art form for me. Some readers might be surprised at this, since my poems often feel very intimate to readers, but with poetry I have more control over what gets revealed and what doesn't. When I was finishing my Masters degree, I seriously considered going into medicine. And finally, after my PhD, I thought about taking the civil service exam and seeing about becoming a diplomat -- in fact, I had some encouragement from diplomats I knew to give this a try. The last is the only one I think of with any real pangs now; I still think I might have made a really interesting life that way, writing poems all the while.

3. The appearance of a poem on the page: how important is this in your view? Do you spend a lot of time with the layout of your own poems?

I care about this very much. Of course, a lot of my poems are formal -- "Dog Days" is a sonnet -- so their appearance on the page is in some way predetermined. But even there, decisions can be made. Will the stanzas be separated by white space, or will the sonnet appear as a single block? White space is crucial in determining both pacing and music in the poem -- music for the eye, but also for the inner voice of the reader. It also is important in revealing the contours of mind the poet has tried to make present in the poem.

NOTES

- The opening quote is from an online piece Coles wrote in 2011 for "The Antarctic Sun," the official news website for the United States Antarctic Program (USAP).

- Coles recently edited the anthology "Blueprints: Bringing Poetry into Communities." A project of the Harriet Monroe Poetry Institute, this book is available as a complimentary PDF at http://www.uofupress.com/portal/site/uofupress

- "Dog Days" appeared in 2010 in "Able Muse," a review of poetry, prose and art. There is a video on the Able Muse site with Coles reading this poem: http://www.ablemuse.com/v9/poetry/katharine-coles/dog-days

Dog Days

Then there are the questions of the body.

What holds it together? What falls

Apart? All of us are faltering, all

In our own ways going rough and shoddy:

My love's arthritic foot and knee; my back

Doubly ruptured, and I was only sitting down.

But these two -- they don't think to complain.

They just keep their noses to the track,

Tracking delights of passage, every smell

Of every passerby bearing the now

Along in its delicious ripeness, enough.

Could it be enough for us? Leave well

Enough alone, I always say. He says

Every dog has her day every day.